Default monopolies

Edition 12. Is COVID-19 the Benjen Stark for tech giants? Why is Death Diving popular in Norway?

Welcome to the 30 new subscribers since last week! I am thrilled that you are sharing the newsletter and sending me great feedback. This takes a fair amount of time to put together and you all have been a great source of motivation! Please continue sharing and tweeting about the newsletter if you like it.

Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman is a sparkling book. It argues that humans have two ways of thinking – System 1 and 2.

System 1 is the intuitive, “gut reaction” way of thinking and making decisions. System 2 is the analytical, “critical thinking” way of making decisions. System 1 forms “first impressions” and often is the reason why we jump to conclusions. System 2 does reflection, problem-solving, and analysis.

Most of us would consider ourselves as System 2 thinkers. Our very sense of identity rests on our belief that we make our own choices. Well, too bad! Daniel Kahneman blows this apart by showing that we spend almost all of our life in System 1, using System 2 only when we stumble across something unexpected (think of replying to a meeting invite over email vs crafting a carefully considered mail to a new client)

Thus, lies the power of defaults. It is simply cognitively more comfortable for us to trust the default option. This power manifests itself in various ways.

Take the political impact for example. New research is indicating that COVID-19 lockdowns have increased support for incumbents, trust in government, and satisfaction with democracy.

Even Donald Trump has seen his ratings improve during the crisis despite the fiasco playing out in the USA.

Given this, it is no surprise that the tech-lash that gripped much of 2019 against the behemoths such as Facebook and Amazon seems to be over. The crisis has provided the tech giants with a once in a lifetime opportunity to consolidate market power and assert dominance while enjoying increasing public approval.

How did it happen? What does it tell us about the future?

Let’s dive into this rapid and fascinating shift today.

2019 was a bleak year for the tech-giants. Their profits soared while public approval cratered.

There was a raft of lawsuits, fines and talks of imminent break-up of these companies. Influential political voices such as Senator Elizabeth Warren in the USA led the chorus. Even Sacha Baron Cohen, the purveyor of characters such as Ali G and Borat, called them the biggest propaganda machine in history. Going further, he argued that Facebook would have even run ads by Hitler.

The tech-giants desperately needed a deus-ex-machina.

Or better known to the Game of Thrones writers as

Enter the Coronavirus

Just like that, the world changed leading to a few remarkable shifts.

Digital platforms provided an alternative. Internet as a digital highway infrastructure held up remarkably well despite the surge. Activities which required physical presence were rapidly transformed using this highway to create digital alternatives. In many cases, such as working remotely, it is argued that it has led to a *productivity boost*.

Our habits changed. As I have written earlier, as people try out new tools, their lives adjust around it. It becomes a habit.

Notice the overall increase. Suddenly, once niche activities - remote workout, telemedicine, do not seem that niche anymore. It becomes a habit.

Tech giants seized the moment. Facebook, Amazon, Google etc. moved remarkably quickly to seize the opportunity provided by the lockdown both within their platforms and at the community level.

Information from World Health Organization on COVID-19 was displayed prominently. But they went further. N-95 masks were donated. Facebook pledged $100 million in grants to small businesses; Google is developing a website for people to self-test for COVID-19, and Amazon said it would hire 100,000 people.

The actions resemble those of a government at a time when administrative capacity is creaking across countries. Julia Wong writes in the Guardian on Amazon.

The hiring of 100,000 staff and a $2-an-hour pay raise is akin to a 21st-century Works Progress Administration (WPA), only private. Amazon’s hometown noblesse oblige – extending its beneficence to small businesses around its Seattle offices so that they might live to serve Amazonians another day – is akin to a government stimulus package. Amazon’s decision to stop accepting non-essential products from third-party sellers who use its warehouses is essentially Amazon regulating the marketplace.

So, what are the results?

Goodwill. From the New York Times

After four years in which social media has been viewed as an antisocial force, the crisis is revealing something surprising, and a bit retro: Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and others can actually deliver on their old promise to democratize information and organize communities, and on their newer promise to drain the toxic information swamp.

Easing of anti-trust regulations. Increased government dependence on the tech-giants and their increasing approval is easing anti-trust concerns. It is hard to engage in mental gymnastics about the harm that Facebook does to the world when we are completely reliant on its platforms to get an escape and be in touch with our loved ones.

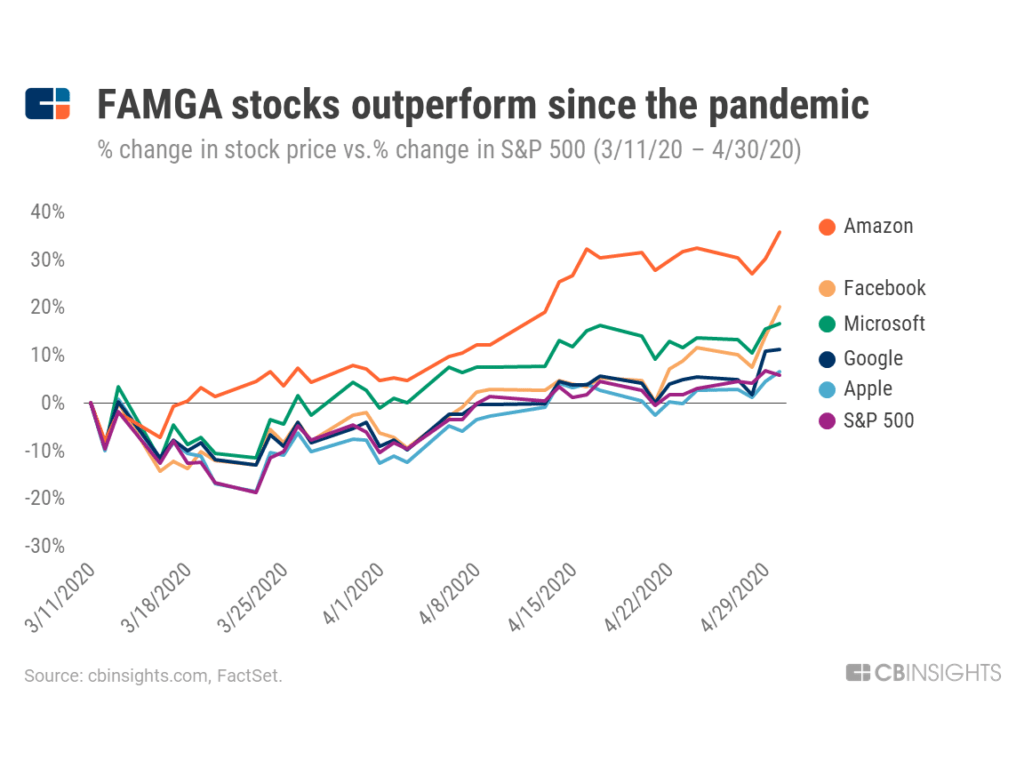

The market has rewarded the giants.

They have used the opportunity to go shopping. Consider Apple. It has acquired 4 companies this year, 3 of which were done after the outbreak of the pandemic. The example of Amazon and Deliveroo is even more striking.

Amazon said last May that it was joining a $575 million fund-raising round, valuing Deliveroo at perhaps as much as $4 billion. Britain’s Competition and Markets Authority halted the deal because it thought it might be bad for competition.

That was before the pandemic.

Deliveroo argued that, without Amazon’s money, it would have to shut down. The British antitrust authority backed down, saying that if Deliveroo went bust, it “could mean that some customers are cut off from online food delivery altogether, with others facing higher prices or a reduction in service quality.”

Expect this to be repeated elsewhere. In the U.S., big companies will take advantage of the so-called failing firm exemption to antitrust law. This doctrine, which dates from a 1930 Supreme Court case, allows otherwise anticompetitive deals to succeed when the target would probably fail without the deal and there is no other viable investment.

The power has simply shifted in favour of resilient balance sheets.

Increased collaboration with the government. While collaboration between big-tech and the government is by itself not new, the pandemic has provided the tech giants with an unparalleled opportunity to supplement government capacity.

Apple and Google have rolled out their own contact tracing initiative to notify users who might have sustained exposure to a person with COVID-19 infection. Even the UK is now considering ditching its own contact tracing initiative and adopting the one by Apple and Google. As Casy Newton puts it in this well-argued piece.

They own the hardware, they own the software, and national governments who would use it to find new cases of COVID-19 have to do it on the companies’ terms.

This phenomenon is not limited to the USA or the UK. As I had written in an earlier piece, in China, the tech-giants – Alibaba and Tencent – rolled out color-coded QR based systems to allow movement of people based on an assigned risk factor. These now form the backbone of the post-COVID reopening of the economy with the result that

The best data lies in the hands of private companies such as Alibaba and Tencent. Taken together, the apps used by the average Chinese city dweller over the course of a day could plot not only their GPS location but every store they had shopped at, meal they had ordered, ride they had hailed, friend they had messaged for meet-up plans and even the rental-bike handles they had touched.

No wonder, the government is reliant on the data generated by the tech-giants to better calibrate their responses. This has led to an incredible scenario where even France, the vanguard of user privacy data law, requested Apple and Google to lower their privacy standards.

This is the natural endpoint of an online privacy debate that has always been more about culture war and competition policy than actual, empirical evidence of harm. The moment there is a need for a reasonable balance of equities, ten years of European rhetoric just evaporates.“France urges Apple and Google to ease privacy rules” is a headline I never expected to see https://t.co/0GxkN4fIpM

This is the natural endpoint of an online privacy debate that has always been more about culture war and competition policy than actual, empirical evidence of harm. The moment there is a need for a reasonable balance of equities, ten years of European rhetoric just evaporates.“France urges Apple and Google to ease privacy rules” is a headline I never expected to see https://t.co/0GxkN4fIpM Alec 🌐 @AlecStapp

Alec 🌐 @AlecStapp

What does the future hold?

This great piece by John Luttig argues that tailwinds are vanishing from the internet economy. The growth rates across a whole class of internet-enabled companies are plateauing.

Half of the global population already has a smartphone. In rich countries, that number often is >80%. On average, people are spending 5+ hours on the phone

People can’t spend more than 100% of their time or money on the Internet. As we approach full online penetration, new companies will need to steal revenue and users from Internet incumbents to grow.

Cost of acquiring new users will increase. It will be increasingly common to see companies winning due to greater spend on marketing than radically new internet-enabled technologies. Simply put, there are not many Uber / Airbnb like markets left to unlock on a global scale.

Tech companies will have to live with a reality of slow and incremental growth. With the gospel of growth thrown out of the window in the post COVID-19 world, the prospects of many highly valued start-ups look dim. Companies with strong balance sheets can make acquisitions and spend on marketing, hence positioning themselves better to win in this world i.e. the tech-giants.

At a broader level, there are two narratives.

One that supports the consolidation of corporate assets under the control of a few rewarding them for their efficiency. The other argues for public control of social assets through regulated competition.

In the first narrative, Amazon has won because it was simply a better manager of capital and invested in future-proofed technologies allowing it to reap the benefits today. In the second narrative, Amazon has decimated competition so thoroughly that it has now become an essential service forcing people to rely on it.

The difference in these narratives is not technical but political. Matt Stoler, the author of Goliath: The Hundred Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy argues that our reality would probably have been different if

we regulated our markets to facilitate more competition in niche software markets or impose public utility rules recognizing the semi-public nature of these enterprises.

Yet, it is hard to shake off the feeling that the moment has passed. Big-tech, for good and bad, is here to stay. Public activism has built pressure on them to do the right thing as this crisis struck. Maybe, that is the playbook that needs to stay active in a world of default tech monopolies.

In other news

A round up of a few interesting things I came across this week.

The post this week was provoked by this thoughtful essay by Tanay Jaipuria, The Power of Defaults. I recommend you check it out.

Another inspiration for this week’s post was this remarkable piece in the Atlantic. As society closed around it, the internet kept running. It is a remarkable system that delivered.

Live-streaming in China is routinely covered in China in the context of hawking low priced products to the emerging internet users. Well, it also saved these farmers during the pandemic. Live-streaming is here to stay.

The pandemic has forced slow-moving giants to innovate rapidly. A few amazing examples in this piece in the Economist. Apparently, 3d cameras are selling like loo rolls.

My find of the week is the sport of Dødsing - an extreme sport based out of Norway. It is basically a riskier version of diving. It consists of people jumping from a 10-metre-high board and landing in the water with their arms and legs spread out like an “X”, and they need to hold the pose for as long as possible before they hit the water. What makes it ‘fun’ is the risk of painful belly flops. Yes, this looks as thrilling to watch as it sounds.

A sport which, according to last year’s world champion, Truls Torp (18), could only have been invented in Norway:

“It’s just how Norwegians are. We’re all totally insane,” he says.

Good on you Norway, for the gift.

130+ subscribers get their weekly insights from this newsletter. If you like it, earn good karma by sharing it with others who might like it too. Feel free to send suggestions on twitter at @romit_ud or at romitnewsletter@gmail.com. Stay safe!