Global Pandemics - a throwback

Edition 13. What does the history of pandemics tell us about the future of our world? Was the Yersina pestis infected rodent more egalitarian than Thanos?

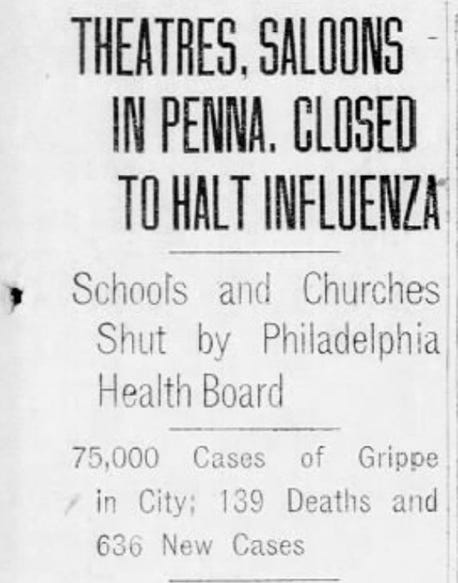

In response to the influenza pandemic in 1918 (‘Spanish flu’), the city councils in the USA issued a few advisories.

Seems familiar?

The history of pandemics is the history of mankind. They have led to the rise and fall of empires and contributed to the ebbs and flows of wealth.

I want to use this edition to look at the two most monumental pandemics in human history – the Black Death and the ‘Spanish flu’. While there were no management consultants to tell us so, these pandemics too upended the world and created a ‘new normal’.

History has a tendency to repeat itself. Studying the impact of these pandemics gives us a directional compass to understand the way in which things may pan out.

It is an epic tale of widespread calamity, the rise of nations, and the resurgence of wealth. Buckle in!

Black Death

In the late 1330s and early 1340s, Europeans started hearing rumours about a ‘Great Pestilence’ that was carving a deadly path across the trade routes of the Near and Far East. In October 1344, 12 ships from the Black Sea docked in Sicily at Messina. People at the port were met with a horrifying surprise.

Most sailors aboard the ships were dead, and those still alive were gravely ill and covered in black boils that oozed blood and pus. Sicilian authorities hastily ordered the fleet of “death ships” out of the harbor, but it was too late.

The expelled ships carried with them fleas infected with bacteria – Yersina pestis, which bred on rats and spread through the air and bites of fleas. These infested ships made their way across Europe unleashing a level of devastation that was unseen then and has been unseen since.

This paper by Sevket Pamuk computed an eye-popping chart of the population (in 000s) of a few European countries.

Notice that within 50 years, the population of Europe reduced by a third. Waves after waves of Black Death in the 14th century inflicted a level of mortality from which the entire continent took over 200 years to recover. Generations bore their brunt without respite. In countries such as Egypt, repeated waves led to the population not returning to pre-Black-Death levels till the 19th century. The enemy was relentless.

Unsurprisingly, such rapid and sustained demographic changes led to monumental shifts in industry, economy and power equation among countries.

Rise in wages. Notice the precipitous drop in population in England (blue line) and the corresponding increase in wages (red line) as, to put it euphemistically’, the supply of labor decreased (i.e. people died).

This was not limited to England. Notice the chart below on relative wage levels across major world cities (mostly European).

Two things immediately caught my eye.

1. The jump in wage levels near 1350 which sustained for over 200 years.

2. For a few cities (London, Antwerp, Amsterdam), wages continued to stay high till the 18th century while it declined back to pre-Black-Death levels for others (cities in south Europe). Let’s come back to this in just a bit.

Higher quality of life. Fewer laborers and higher wages landed feudalism in trouble. The system of bonded laborers slowly dissipated as the concept of commercial farming took hold. Higher per capita income increased demand for luxury goods. People drank more beer for example.

Demand for, and prices of, wheat went down, while the prices of meat, cheese and barley held up, the latter due to the growing demand for beer, which may be taken as a good indicator for higher standards of living and improvements in the diet.

Mass automation. Businesses invest using debt. Lower rate of interest encourages further borrowing. Flushed with increased earnings, the rate of savings rapidly increased in medieval Europe leading to lower rates of interest.

The borrowing costs for large monarchies fell to 8% to 10% by the early 16th century from 20% to 30% before the Black Death. Florence, Venice and Genoa as well as cities in Germany and Holland saw rates slump to 4% from 15%.

These factors along with increased mobility of labor led to investments in automation and industrialization resulting in groundbreaking innovations such as the printing press.

The growth of universities in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and the expanding numbers of literate laymen had generated strong demand for books. Scribes had been employed to copy manuscripts. With the sharp rise in wages, this labour-intensive method ran into difficulties. Gutenberg’s invention of printing on the basis of movable metal type in 1453 was only the culmination of many experiments undertaken during the previous century.

Firearms, another innovation of this era, can also be interpreted in these terms.

New world powers were born. The biggest geopolitical impact of the Black Death was the great divergence within Europe. Before Black Death, the Mediterranean countries were richer than countries like England the Holland which were considered to be ‘agrarian peripheries’. Then the pandemic struck.

By 1800 the situation was largely reversed. First the Netherlands, then Britain developed into commercial and manufacturing centres with large urban economies. In contrast, Italy and Spain lagged behind.

As the chart above showed, wages declined in Mediterranean countries while they continued rising in northern countries.

There are multiple reasons theorized for this dramatic shift but a major one seems to be a more gender-equal workforce in England and Holland.

The average age of marriage for women increased in England to mid-twenties while it stayed low in countries like Italy. Delayed marriages led to increased female participation in the workforce and slower population growth resulting in greater savings.

Increased prosperity, rapid automation, increase in secular beliefs due to the decline of the church ultimately led to the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution. The world was never the same again.

Influenza outbreak (‘Spanish Flu’)

The origins of the flu are unclear. However, what is clear that it did not originate in Spain. As I had written in an earlier post

While the origins of the flu in 1917 in the midst of the First World War are unclear, it was certainly not Spain. The press in the UK and the US censored their media on covering the flu to keep the morale of their troops high. Spain was not a participant in the war and had no media censorship. It’s press covered it freely. The messenger was shot and it was dubbed as the ‘Spanish flu’.

The flu was first observed in Europe, America, and areas of Asia before spreading across the planet in a matter of months. Unlike normal flu, it mostly killed young and healthy people. In fact, more U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the first World War. The flu is estimated to have infected over 500 million people globally and killed ~40 million.

The major US cities responded then as they have today. Calls for social distancing were issued and people were advised to stay home. However, what is striking is the limited economic impact the pandemic had on the economy compared to COVID-19.

The unemployment showed only a minor spike.

Industrial production returned to pre-plague levels quickly resulting in the infamous era of ‘roaring 20s’.

Few key reasons account for this difference. For one, manufacturing and agriculture formed a much larger share of employment in the USA. These industries were less susceptible to the flu compared to the services industry which dominates the economy today. Government spending was also extremely high due to World War One, moreover, mandates were issued to keep industries open due to pressing demand for industrial goods. This acted as a natural stimulus. Cities themselves were less dense compared to today and limited communication and media suppression did not let the true picture emerge.

Unlike Black Death, there were only 2 major waves of the virus, once it passed by 1919, things largely returned to normal.

However, it was not all hunky-dory. Research shows that retail businesses were impacted then as they are today. Wages in hardest-hit cities increased leading to greater growth once the flu passed. Capital intensive production accelerated as well as higher wages incentivized investments in capital.

An often-ignored fact of the flu is that its highest burden was borne by India. 5% of India’s population – 15 - 18 million succumbed the flu. A rapidly rising mass politician, Mohandas Gandhi was infected by it too.

The pandemic devastated India. In certain districts in central and east India, the mortality rate was as high as 10%. The life expectancy at birth which was already at a pitiable 23 in 1911 fell to 20 by 1921. Tragically, much like today - the disproportionate impact was felt by the unprivileged.

In Bombay City mortality among low caste (and presumable poorer) Hindus was 3 times that of other Hindus, and more than 8 times that of Europeans.

However, the second-order impact of the flu was increased fertility in women and also a better quality of life for newborn children. There was an increase in levels of nutrition and literacy, especially among boys. The districts with a high rate of mortality also saw a rise in average wages resulting in greater migration back to those districts.

In a way, the flu brought forth now accepted means of combating a pandemic - #flattenthecurve and shed light on sharp inequities. India, which saw more casualties than all of World War One combined, has been reduced to a footnote when the story of this flu is told.

COVID-19. Is history repeating itself?

This is speculative but a few clear trends are emerging that mirror what we have seen in the pandemics above.

The government can save economies. The war effort during the Spanish flu possibly saved the economy. The tepid responses of weakened kingdoms of Europe during Black death did not. Government has the power to stop job losses and stem the bleeding. The last couple of months has shown that if they are willing to exercise it, the economic damage could be limited.

Low-interest rate regime. Before the coronavirus struck, the interest rates still had not reached pre-2008 levels. They are now down to zero again. As interest rates plummeted across Europe in the aftermath of Black Death, kingdoms invested more in arms leading to state deficits. Countries today will also binge on cheap debt to finance their economies. Things can turn awry especially for emerging economies if the debt crisis blows up in the future.

Labor migration. Pandemics have been characterized by labor mobility. As remote work is rapidly normalized, there is a de-coupling of providing labor as a service and physical proximity. Are we moving towards a world where a Silicon Valley firm could potentially hire engineers from China and India without requiring the engineers to move to the USA? Possibly. The best firms might find the best talent with greater ease and correspondingly the best talent might find it easier to recruit for their dream firms. All remotely of course.

Increased automation. The Black Death led to the job of the scribe being automated as the printing press was invented. COVID-19 will also lead to new forms of automation. Routine jobs are increasingly at risk. According to Brookings

Robots’ infiltration of the workforce doesn’t occur at a steady, gradual pace. Instead, automation happens in bursts, concentrated especially in bad times such as in the wake of economic shocks, when humans become relatively more expensive as firms’ revenues rapidly decline. At these moments, employers shed less-skilled workers and replace them with technology and higher-skilled workers.

Increase in wages. As routine jobs get automated, returns to specialized education will increase. Skilled laborers saw a sustained increase in their earnings after the Black Death and the influenza outbreak. This time will be no different. Supply of specialized ‘skill-intensive’ STEM courses will increase so will their demand. Specialised skills in design, coding, services will see increasing returns. In fact, early trends show exactly this result.

Great divergence. Much like the shift in the power equation in Europe post-Black Death, there is a clear shift happening in the global power equation due to COVID-19. Europe, abandoned by its transatlantic ally, USA, is mired in internal strife as stronger economies such as Germany increasingly turn inwards. Meanwhile, so atrocious has been USA’s response that it resembles more a failed state than a world superpower. Lawrance Summers, the renowned economist, summarizes it masterfully in this brilliant piece

Covid-19 may mark a transition from western democratic leadership of the global system. The performance of the US government during the crisis has been dismal. Basic tasks such as ensuring the availability of masks for health workers who treat the sick have not been performed. Medium-term planning has been conspicuous by its absence. Elementary safety protocols have been ignored in the White House, putting the safety of leaders at risk.

Yet, For all of the Trump administration’s manifest failures, the US has not been a particularly poor performer compared to the rest of the west. The UK, France, Spain, Italy and many others all have Covid-19 death rates per capita well above the US. In contrast, China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand all have death rates well under 5 per cent of American levels. The idea that China would be airlifting basic health equipment to the US would have been inconceivable even a year ago. If the 21st century turns out to be an Asian century as the 20th was an American one, the pandemic may well be remembered as the turning point. We are living through not just dramatic events but what may well be a hinge in history.

Long term impacts of such massive shocks are impossible to model. When the Black Death struck, no one could have predicted that a disease causing black boils oozing pus and blood would lead to the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution. If history is anything to go by, COVID-19 will shape not only our lives but those who come after us. It will be another new normal.

I rely on you to spread the word about this newsletter. If you like it, please continue to share the newsletter, and send me your feedback. It keeps me going!