As a kid growing up in Varanasi in 90s India (a ‘small’ town with fewer than a million people), I distinctly remember the first ice cream parlor that opened near my house. A refuge from the banality of Vadilal icecreams that dominated the town, it was a social setting for people to meet, feel aspirational, and occasionally eat an ice-cream.

I eventually moved to Bombay. The glitzy malls supercharged that experience. Many Sundays were spent not necessarily shopping but strolling past shops, discovering trends, and often ending with a photo next to Ronald McDonald under the golden arches.

14% of all global retail sales now happen online. Yet much of the experience feels humdrum. The elements that made offline shopping fun – discovery, social, and fun are entirely missing from an ML optimized algorithm-driven online experience.

This simple insight has led to the rise of a remarkable e-commerce company. Unsurprisingly, the company was birthed in a market which is the vanguard of the online commerce experience - China.

Does it herald the future of our online experience or is it something else entirely once we look under the hood? Let’s dive in.

If you think someone might find these weekly summaries interesting, do share it with them!

Note the rapid growth of a third platform starting in 2017.

Pinduoduo (PDD) is the fastest-growing e-commerce platform in a country with 800 million online shoppers spending over $1.5 trillion annually - ~2.5X of the total US online commerce spend.

PDD's fundamental value proposition to users is that it is often the cheapest platform for them to buy goods.

How does it work?

A short explainer of the concept below.

PDD encourages its users to buy in groups. A person could buy a product for a certain price but they are encouraged to get a group of friends and family to buy products at the same time, allowing the whole group to get further discounts. Look at the order flow for Airpods from the Apple store in China compared to PDD.

A shopper can join an existing group or start a new group to get further discounts from the listed price.

How does it keep the prices low?

This is from the CEO of the company in an earnings call.

People who are unfamiliar with our platform, sometimes question how products on our platform can be so affordable priced. The differentiation is such that, unlike other platforms with simply bringing offline sales online. We enable merchants to offer lower-priced prices by aggregating the collective needs of our users. The purchase model transforms demand that would it be otherwise scattered across different SKUs at a time horizons into the demand that is in a single time frame and on fewer SKUs

The group-buying model also dramatically lowers the cost of acquiring a customer (CAC). PDD’s CAC is estimated to be $1.64, a fraction of those of Alibaba Taobao’s $46 or JD.com’s $35.

Group buying transactions are ideally greased by overlaying a social layer that connects friends and family. WeChat (owned by Tencent) happens to be that platform in China. The platform bakes in the feature of mini-programs - ‘Lite apps’ that can be shared quickly without leaving the walled garden or requiring users to download a separate app. PDD went viral on WeChat. As recently as 2018, 65% of its total transactions flowed through this mini-program. Spotting an opportunity to expand into commerce, Tencent moved to lead PDD’s Series B round of funding in 2016.

The rise of live streaming

Xerox Corp’s Palo Alto Research Centre is legendary. In pop-culture, it is portrayed as the place where Steve Jobs saw the mouse and graphical user interface (icons et al) for the first time. He was ‘inspired’ to replicate it at Apple and the rest is history.

Turns out that is not the only category-creating innovation from the center.

In 1993, an obscure garage band - Severe Tire Damage hosted the first live stream from the same research center. Today, live streaming has upended video consumption habits of millions globally and turbo-charged the growth of online commerce in China.

The world’s largest internet-enabled population has created numerous social media stars, capable of attracting millions to their streams and wielding tremendous power to push products by influencing purchase decisions. There are even academies to train ‘influencers’ where businesses identify promising talent and groom them to create content and build an online following.

Take the case of Li Jiaqi.

27-year-old, he was a shop assistant for L’Oréal in Nanchang, a second-tier city in China. He is now a celebrity with 40 million followers on Douyin (TikTok in China) and a net worth in millions.

As you might have guessed, he live streams and sells beauty products online - specifically lipstick. Unlike most beauty vloggers, he applies lipsticks on his lips rather than his arms to show how they actually look. So popular are his streams that on Singles day - China’s largest shopping festival started by Alibaba, he generated sales of $145 million alone while attracting an audience of 36 million people.

That is him live streaming lipstick reviews with Jack Ma on Taobao Live. No wonder he is dubbed 'The Lipstick King’.

PDD has innovated on top its core proposition of group buying and invested heavily in live streaming. It has also followed a customer to manufacturer (C2M) strategy where manufacturers and producers themselves host live streams sharing their products and the stories behind them. Customers can interact with the manufacturers and producers during these live streams, and of course, purchase these products (along with their ‘group’).

PDD does not actually hold any inventory. Items are directly shipped by sellers who also bear the shipping costs. PDD thus runs an asset-light operation that simply connects buyers and sellers.

A massive ad platform

Interestingly, unlike most e-commerce firms, PDD does not make substantial revenues by taking a cut of the transaction value. Last year it made 89% of its revenues from online marketing. Merchants paid PDD to display their products and streams as ads to prospective buyers to boost sales.

That is key to understanding the platform. A monetization model like this means that PDD is not in the e-commerce space, it is in the ‘capturing eyeballs’ space.

Any advertising platform’s ability to monetize increases dramatically as more users come on board and spend more time on it (Facebook, Google, TikTok, YouTube, etc.) PDD gets its views by surfacing interesting products, hosting live streams, and promising cheaper prices if an existing ‘eyeball’ brings more. It has gone further, investing heavily in social features such as gaming to grab and keep those eyeballs. This Y Combinator piece does a great product teardown.

The rapid growth of PDD

In just 5 years since inception, PDD claims that Gross Merchandise Value (GMV) of goods flowing through the platform for 12 months ending March 2020 topped $163B. To place that in context, that figure is half of the total GMV of Amazon globally, ~3x of Shopify’s GMV, and greater than 5x of total e-commerce GMV of India. A staggering statistic, especially considering that the company is just over five years old. PDD claims to have ~630 million active buyers of which ~450 million shop at least once a month and spend ~$260 annually on PDD. Starting out as a viral platform in smaller towns, it has made rapid inroads into larger cities in China as well with Tier 1 and 2 cities contributing to 45% of total GMV.

Revenues have grown an eye-watering 17x from 2017 reaching $4.3B in the financial year ending 2019. Unperturbed by COVID-19, the company clocked impressive Q12020 numbers bringing ~$925 million in revenues in what is typically a lean quarter for online commerce.

Is PDD ready to be the new king?

Not just yet.

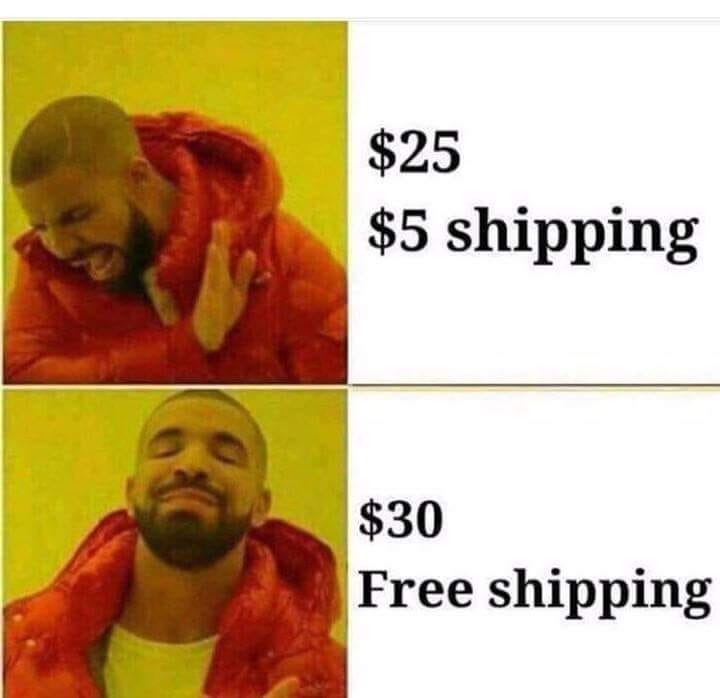

The financials also narrate a worrying trend - excess spending on sales and marketing. Look at the picture above comparing purchasing Airpods online on Apple store vs PDD again. Notice that the original Apple Airpods are cheaper on PDD than the official Apple site itself.

The current PDD is the biggest bubble in the history of China’s internet.

Guosheng Securities Research Institute

Analysts have cast doubt over the business model which they believe pays merchants to artificially lower the prices and inflates the GMV numbers. PDD has launched the longest-running ‘subsidy program’ ( in the history of e-commerce in China entailing outsized marketing spends.

For context, the total outlay on marketing in Q12020 was greater than the revenue itself ($1.03B vs $925M).

It was not a one-off quarter. This has been the case for almost every quarter of PDD’s existence.

Large marketing spends has racked up the losses. PDD listed on the NASDAQ in July 2018 (raising $1.7B) and has raised an additional $3.3B over three fundraising rounds since. In response, PDD claims that it is still a ‘start-up’ and is investing in growth against much larger and deep-pocketed rivals. The core business itself is profitable with gross margins over 70%.

That is a little too clever.

Given that PDD is in the advertising business, gross margin is expected to be high since the largest cost is server. To be profitable, PDD needs to increase the share that is spent by the merchants and/or needs to monetize transactions aggressively. Both have challenges.

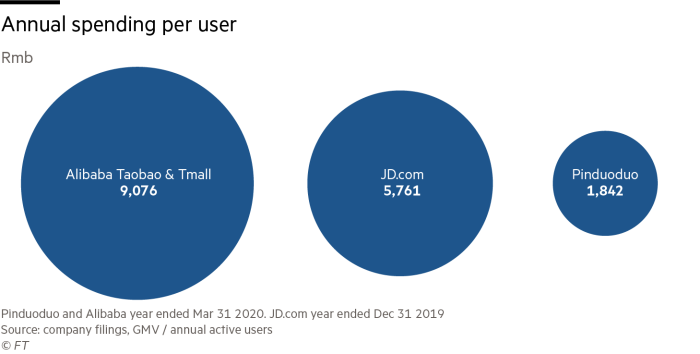

GMV between 2018 and 2019 grew by over 110% while the spend per merchant on ad services grew by only 64%. On average a merchant spends only $61/month in advertising on the platform - a number that needs to increase substantially. On the other hand, an average user on PDD spends ~1/5th of the average spend on Alibaba’s platforms.

Its core proposition of value has attracted users looking primarily for deals. They are often purchasing essentials such as agricultural goods which constitutes ~15% of total GMV on the platform. Shipping is also borne by the merchants leaving razor-thin margins on the table.

Competition too has responded in kind. Alibaba has launched an RMB 10 billion subsidy program of its own. It has also launched Taoxiaopu - a ‘reseller’ marketplace, in an attempt to capture the growing social commerce market in smaller towns - the same that had initially propelled PDD.

Larger platforms (Alibaba and JD.com) are also flexing their muscles by reportedly getting merchant exclusivity which bar them from listing on competing platforms - a practice that has gained steam even though it is illegal. Even Tencent has made forays in live stream commerce, encroaching on friendly turf. PDD’s explosive growth has been on the back of the near-universal reach of WeChat (owned by Tencent). No doubt it would be watching developments at Tencent closely.

COVID-19, the harbinger of fortune?

COVID-19 has amplified PDD’s ambitions. It has doubled down on smaller towns by investing heavily in increasing the subsidy program, innovated on features within the app, and hosted diverse live streams including museums such as the New York Met to help them sell souvenirs. It has also aggressively onboarded farmers to go deeper into the ‘farm to fork’ fresh produce - a segment gaining traction in larger cities in China.

The craze for live stream has only increased. High-value items such as Teslas and even houses are now being sold online. Higher margin goods flowing through the platform gives it an opportunity to start charging meaningful transaction fees. PDD is also rapidly expanding the C2M strategy and developing in-house brands as more customer data flows through its pipes. All these have the potential to dramatically improve both the top line and the bottom line.

While the analysts have their concerns, PDD’s share price has more than doubled through the pandemic.

PDD is currently trading at a pricey multiple of ~27X trailing twelve months revenue. At a market cap of over $100B, it is the most valuable company in the world never to have made a single quarter of operating profit.

Celebrating now would be premature. PDD has its work cut out before it shuts out the naysayers.

In other news

A round-up of a few cool things I came across this week.

I have been binge-watching incredible stories of online influencers in China. A short video on Li Jiaqi (the Lipstick King) who I covered in the piece above.

Some of you might have read Marc Andresson’s call to arms to build. A great piece on why the rise in venture capital investment has not led to things being built that are truly needed.

Speaking of Marc Andresson, I have been trying to get deeper into breaking down what makes me productive and how can I retain and increase that attention span. This is a great Marc Andresson interview on his productivity hacks, how to set goals, and manage your time. Gave me a lot to think about.

A few of you might have tried out Notion. Marie Poulin runs her life on it and she has made it an art form.

What would your question be?

That is all for the week. If you enjoyed my deep dive and the memes, please share the newsletter on Twitter, Whatsapp (or maybe LinkedIn?). Getting the word out helps me get more diverse feedback which in turn makes this newsletter better. So, do share! Write to me at romitnewsletter@gmail.com or Twitter.