26th August was a momentous day. A cinephile and a believer in the power of the big screen, Christopher Nolan released his latest opus, Tenet[1], across theaters in the USA on that date. Coming after months of theaters being shuttered, the event was widely anticipated to answer a burning question. Can cinemas be saved?

For today’s edition, I want to take a look at what is bedeviling the movie business and what the current trends might tell us about how one of the most powerful communal experiences created by mankind might change as things open (Spoiler alert: Popcorn will still be overpriced!)

First, let’s understand how the economics of a movie works.

Assume that a film is made for $100M, and marketed for another $50M. At this point, the studio producing the movie is $150M in the red. To recoup this, the studios sign a deal with distributors on revenue share from gross ticket sales of theaters. While the number varies, the median is broadly 60%. Hence, for every dollar that a theater earns in sales of tickets, 60 cents would go to the studio. One interesting facet of this transaction is that this share reduces with time to incentivize theaters to screen films longer. Proceeds from a movie’s theatrical run form a bulk of its earnings but certainly not all. Other sources of revenue include streaming rights, cable broadcasting rights, video games, licensed brand deals such as merchandise. These can be substantial, for example, Geroge Lucas (who took a smaller salary to retain full rights to sales from merchandise) famously included Ewoks in Star Wars - Return of the Jedi to sell more toys.

This model was already under pressure pre-COVID-19 due to a few long term shifts.

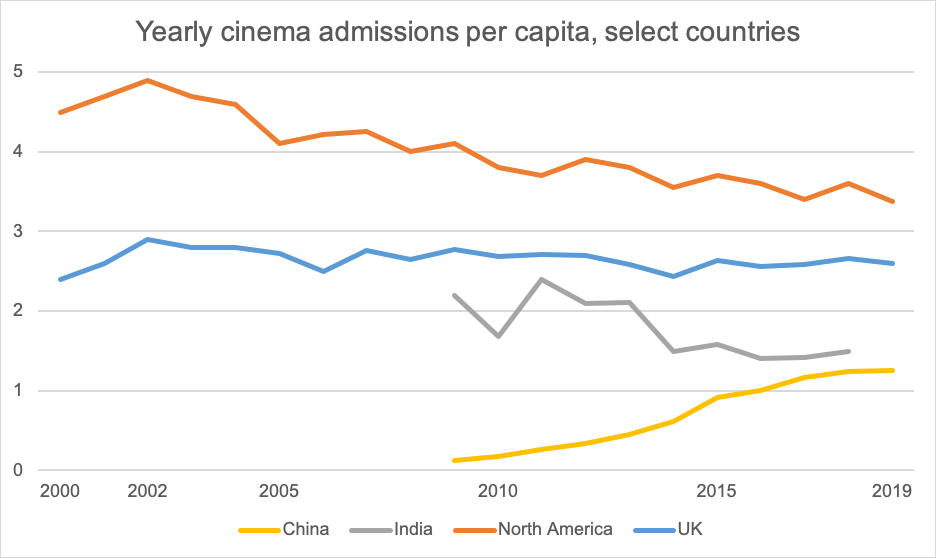

One, in general, attendance in movies has been falling for years.

Except for China, where the audience grew ~10X in a decade ending 2019, most markets are in retreat. Even in India with rapidly rising income and home of the world’s largest film industry by the number of movies made, attendance is in retreat primarily due to a dearth of new screens.

Second, and a related reason, is the steady rise of streaming platforms. In deeply penetrated markets like the USA, nearly 2/3rds of adults have at least one subscription to a streaming service, and over half pay between $10 - 20 for streaming services. I have covered the rapidly increasing subscription of Netflix internationally in an earlier piece.

Interestingly, another trend is at play. Have you ever wondered why the likes of Disney, a media behemoth, do not own their own theaters, allowing it to become a vertically integrated company (from movie production to end mile distribution)?

In 1948, the US Supreme Court passed a ruling against this practice on the grounds that it hurt competition. A similar wave is nevertheless underway now. Large media companies have invested in their own white-labeled media platforms (Disney, HBO in the USA. Zee, Balaji in India). The media houses have used a strategy of ‘exclusives’ (original programming) to drive membership and eyeballs to their platforms. Many of these include original movies, reducing the negotiating power of theaters. Moreover, the media houses also bring movies sooner to their platforms, reducing the hallowed ‘theatrical window’ - the period where the theater is the only avenue to watch the movie. The theatrical window has reduced by more than two months and simultaneous releases (on streaming platforms and theaters) are on the anvil. Something unthinkable even a couple of years ago.

Third, the rise of franchises. Multimodal forms of entertainment (streaming apps, video games) have given rise to franchisees that drive a significant share of revenues outside just the theatrical releases. Disney bought Marvel in 2009 and spawned the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). After releasing 21 movies (Avenger series) that were a part of the same ‘universe’ (timeframe, character interdependencies, storylines, cross movie features), Disney has also created TV spinoffs (Agent of SHIELD) and video games. The success of this model has spawned an era of indistinguishable summer ‘blockbusters’, giving greater power to movie studios like Disney who can strike better deals with theaters, squeezing them further.

As coronavirus conquered the world, cinemas were among the first in the line of fire. As they shut down for months, the impact was tumultuous.

AMC, the largest movie theater chain in the US (and the world) was on the verge of bankruptcy. In India, single-screen theaters are shutting down in the pandemic, often permanently so. The film industry looking for means to cope found a savior in streaming companies who offered them an alternate platform to release their movies.

The existential risk is not lost on the theater chains. INOX (a large multiplex chain in India) has warned of ‘retributive measures’ against studios who go straight to streaming platforms. AMC in the US, briefly boycotted the major production studio - Universal, after the latter insisted that they will henceforth release their movies simultaneously in theatres and streaming platforms.

However, this is not the first time that theaters are facing an existential struggle. The Spanish flu took a toll on the cinemas from 1918 - 1920. In Los Angeles, the home of Hollywood, theaters were shut for over 2 months as Hollywood closed operations.

In a similar echo of the debate today, the lives vs economic cost argument played out a century ago as well. The governments did not take shutting down of theaters lightly.

The British government saw cinema as an essential tool for public well-being. “Cinema was the major leisure activity – it kept people occupied, and it helped keep them calm. It also kept them out of the pubs!” says Napper. “Drunkenness was a major issue for the authorities. But also cinemas became a key site for propaganda and a key point of contact between the individual, the local community and the national war effort.”

The theaters eventually stared again with hygiene measures in place. There was a change in the industry as well as smaller theaters shut down and larger chains emerged.

In the 1950s and 60s, as more households in the USA purchased televisions, theaters were in crisis again. Steven Spielberg released Jaws in 1975 and dawned an era of summer blockbusters (the consequences of which we bear to date) and theaters hung on. Similarly, in the 80s, the theaters responded to the growing threat of VCRs with new a format - plush multiplexes.

What does the future look like?

Theaters remain the most powerful tool for collective immersion. They are unlikely to vanish. Yet, after the previous crisis, they morphed and changed. A similar fate awaits now. Similar to other industries, consolidation is inevitable. Our stand-alone neighborhood cinemas, already on life support, are experiencing their moment of reckoning. Theaters will no doubt invest in hygiene, upgrading the experience to entice viewers (resulting in higher ticket prices and overpriced popcorns). In turn, independent movies will find it hard to make the economics work. We can expect more cerebral and indie movies to come straight to streaming platforms (think the Irishman). Meanwhile, our theater experience could imply fewer trips to experience larger and larger blockbusters.

Comic book movies already outgross films made on original screenplays. That trend has seen a further shot in the arm. Ultimately, superheroes save the day in movies, they may also be needed to save the cinemas.

[1] Tenet grossed $20M in its opening weekend. Not a washout but certainly below expectations and not in a position to ‘save the cinemas’.

In other news

Is free will an illusion when we are moving to a world where large corporations and government know more about us than we ourselves? Yual Noah Harari’s great take on the illusion of will.

Why do so many ‘new-age’ direct to consumer brands look the same?

Chairs were not designed for human bodies. They are also terrible for us. Why is it so hard to design a better one?

The surprisingly contentious and heated history of coffee.

Are we in a ‘K’ shaped economic recovery? What does it even mean?

Update.

Thank you for the feedback that you send every week. I find it extremely valuable and it keeps pushing me to improve. I hope you have enjoyed this journey too. On a personal note, I am taking a break for a couple of weeks. BN(E)W will see you on the other side of the break. Till then, do leave a comment or write to me with suggestions of things that I should cover at romitnewsletter@gmail.com or Twitter.

Hi Romit! Informative as always. Just wanted to add a couple of things I've been noticing after following the industry here.

Multiplex owners and chains have resorted to a wide variety of tactics to get their point across. Initially releasing strongly-worded statements as you said, they then explored drive-in screenings and outdoor cinema as alternatives.

Then, the PVR chairman said that he was confident that people's decades-old viewing habits would not change in 5-6 months. Despite such firm assertions, the multiplex associations have been advertising in newspapers, asking why cinema halls continue to be locked down under every successive "unlock".

They have also been asking for financial bailouts from the government. However, PVR's rights issue in August was still oversubscribed nearly 2.5 times, so maybe their confidence isn't completely misplaced. Interesting to see how it plays out.