The rise of e-commerce rebels

Edition 14. Are open platforms the alternate to e-commerce juggernaut that we need? Did Spotify just rob Joe Rogan by paying him $100 million?

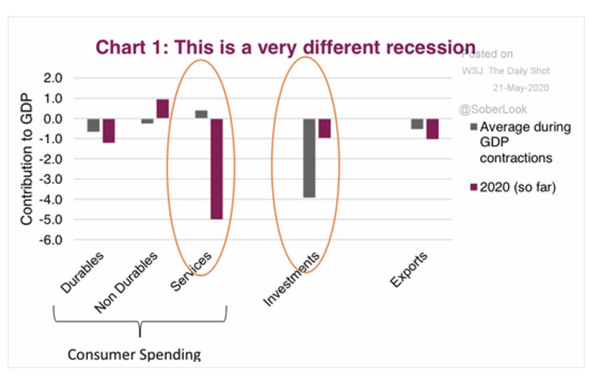

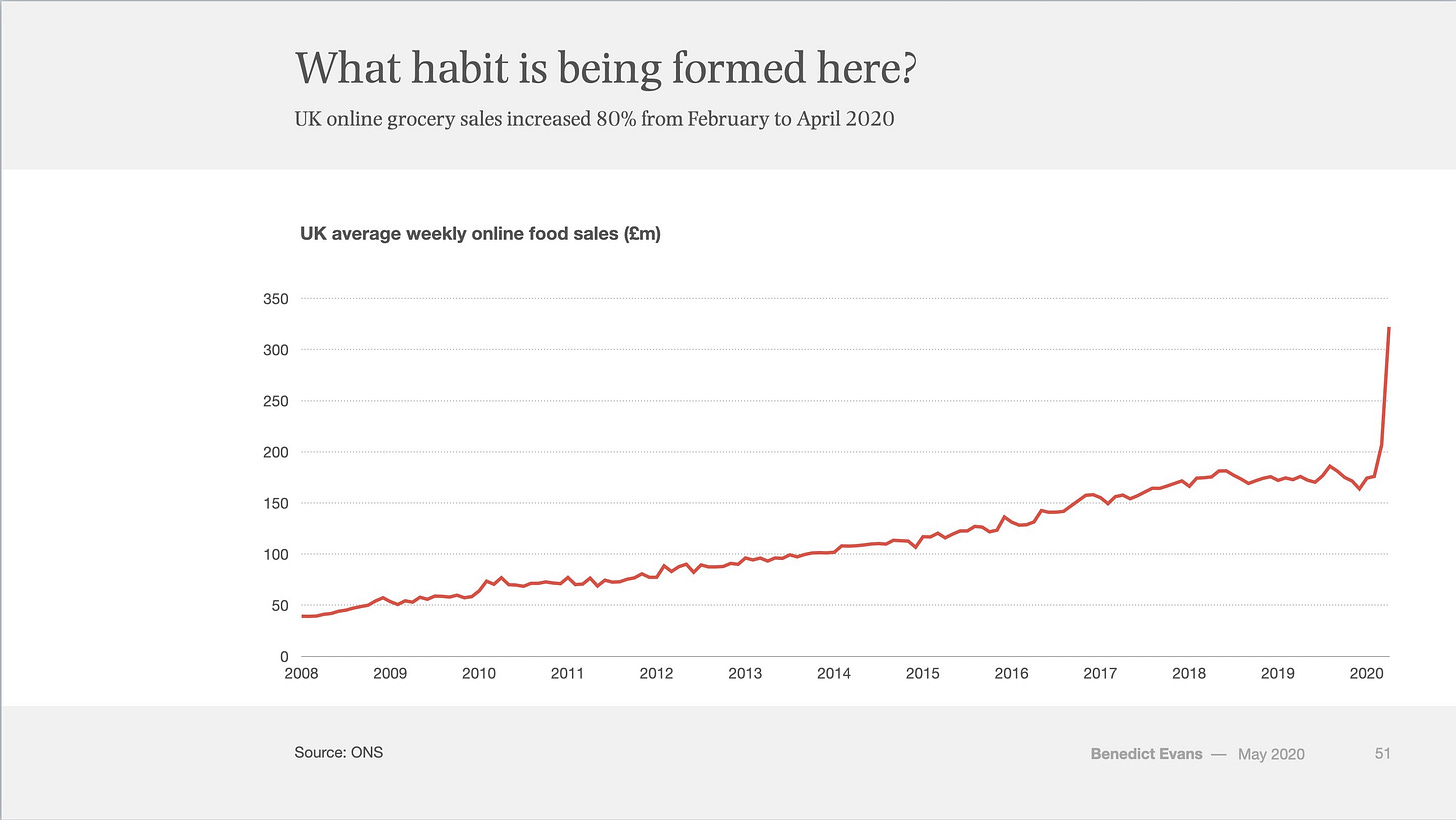

One fascinating phenomenon (amongst many) due to the COVID-19 fallout has been the volume of eye-popping charts that have been created. Never in my life, have I seen the slope or the direction change so rapidly.

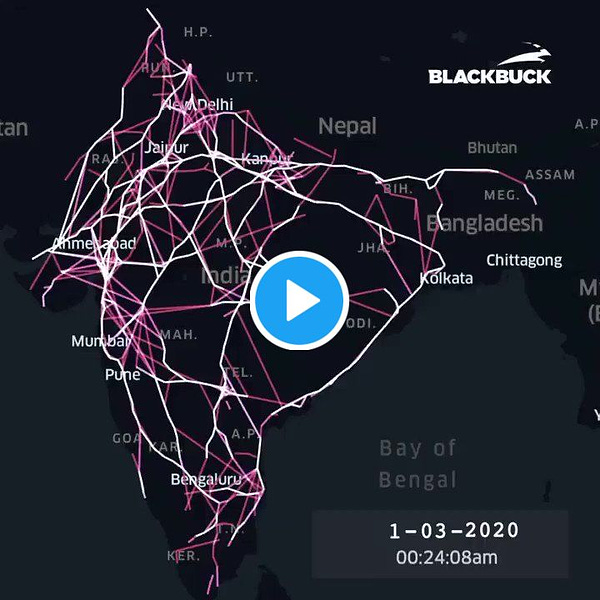

It has also created some cool visualizations

Here are another two such incredible charts.

There has been a plethora of commentary about the rapid rise of digital commerce. The two charts above sum up that trend.

As retail businesses get disrupted, the obvious takeaway might be the increased dominance of hegemons like Amazon. Its sales have skyrocketed and 175,000 people were hired in the last quarter to cope with increased demand. I have also written about increasing likelihood of monopoly of Big Tech in a previous post. While customers have flocked to Amazon, it is probably fair to say that the company does not induce warm cuddly vibes in many.

Is our likely future the one where businesses have to list themselves on a large marketplace like Amazon to survive the disruption? Is the Amazon juggernaut unstoppable?

Not necessarily.

A Canadian company is fast emerging as a major competitor to the all-encompassing behemoth that is Amazon. It’s been in a tearing hurry during the lockdown, introducing features at a furious pace to enlist more of these businesses. Its approach could define an alternate future for digital business, one that is more open and increases choice.

Let’s dig into this company and this trend today.

Why can’t businesses just go online themselves?

Theoretically, they could. Yet, the time and cost for doing so are prohibitive. Going online needs a payment solution, cataloguing, invoicing, and delivery to start with. A business operating at a small scale would find these hurdles almost insurmountable.

Enter marketplaces like Amazon or Flipkart. They promise a source of aggregated demand and build supplier tools to enable businesses to move online.

Yet, there is a catch.

They control the distribution. When was the last time when you bought a product from Amazon or Flipkart and remembered who the seller who sold the product was? Does it even matter? Supplier is a commodified. All that matters is product discovery, delivery and the post-sales experience, tightly controlled by the marketplaces, giving them deeper brand recognition.

The lack of brand recognition leads to a high risk for these businesses of being substituted. It seems that they are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Enter Shopify

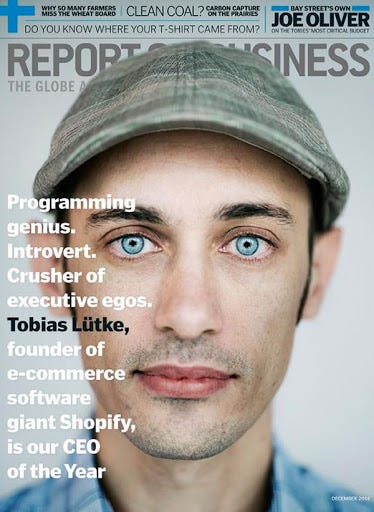

In a very Canadian tale, three men in 2004 wanted to sell snowboarding equipment online. Deeming the existing alternatives to be unsatisfactory, they decided to build their e-commerce platform. One of them was Tobias (Tobi) Lütke; a German-Canadian programming prodigy who by the age of eleven was writing the code of games that he liked playing on his computer. His reputation has grown since.

He has carried his love for video games till date and allows the employees at Shopify to expense games like Factorio, believing that skills learned from one activity (in this case playing the game) can be applied in other contexts (business and problem solving), to great results.

He details his life philosophy including his admiration for stoicism, and learnings further in this thoughtful podcast.

A helpful Twitter thread of his beliefs below -

So, the CEO is cool. But what is Shopify?

To state a cliché in the venture capital industry, it’s a platform.

From Ben Thompson of Stratecherry

At first glance, Shopify isn’t an Amazon competitor at all: after all, there is nothing to buy on Shopify.com. And yet, there were 218 million people that bought products from Shopify without even knowing the company existed.

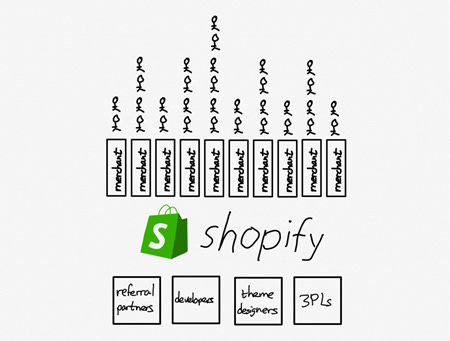

The difference is that Shopify is a platform: instead of interfacing with customers directly, 820,000 3rd-party merchants sit on top of Shopify and are responsible for acquiring all of those customers on their own.

Put simply, merchants can go online on Shopify and set up their independent stores. All they have to worry about is their product and getting demand i.e. a traditional function of a business. Shopify handles everything else. Ben Thompson illustrates this as -

In return, merchants pay Shopify a subscription fee and an additional fee for services used. How simple is it? Well, simple enough that a shop can be set up in under 10 minutes.

Customer (in this case, small business) centricity has been the north star for the company. Two of their core proposition which they identified in their investor document in 2015 when they filed to go public, really stood out.

A Platform Designed to Launch and Grow Brands. Merchants can launch and build their brand on the Shopify platform without any intermediaries or middlemen.

Marketplaces like Amazon are effectively a middleman. They take a cut of all sales by third-party merchants. Shopify is not a middleman. Business websites built on Shopify do not even have a Shopify logo on them. Pay Shopify a subscription or a service fee, and keep all your sales proceeds i.e. independence from middlemen.

An Open Platform with a Thriving Ecosystem. A rich ecosystem of app developers, theme designers and other partners has evolved around the Shopify platform. The Shopify platform’s functionality is highly extensible and can be expanded using our API and apps from the Shopify App Store to offer additional sales channels, bolster features in an existing sales channel and integrate with third-party systems.

Unlike an Amazon which is closed to third-party developers and all features are rolled out by the company, Shopify encourages third-party developers to create tools for business (think an app store equivalent). It provides an open field for competition between multiple businesses both inside and outside the platform.

Growth

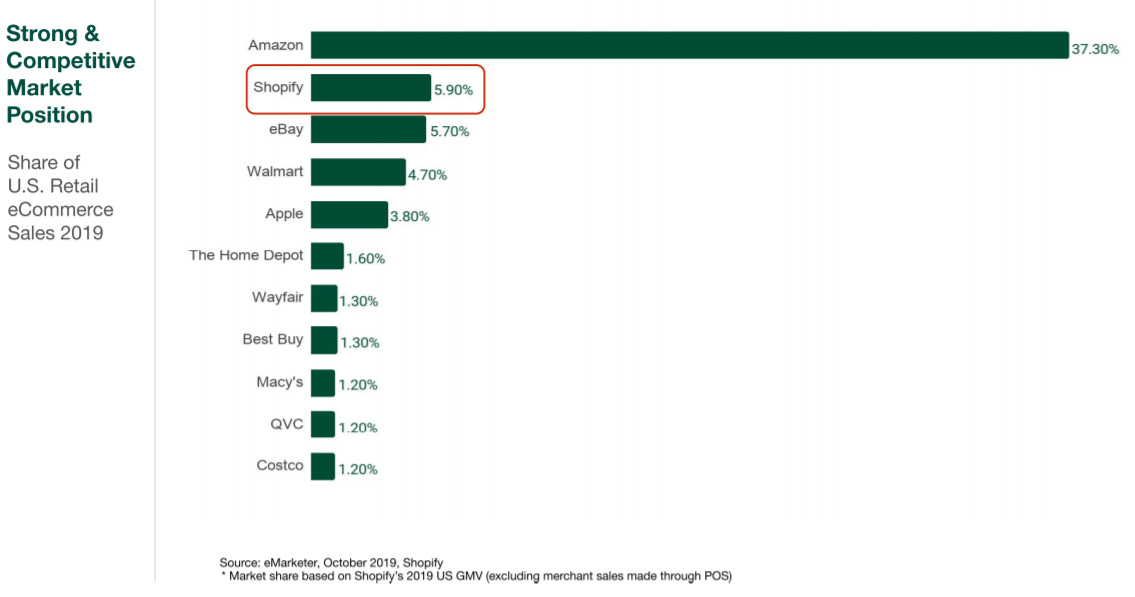

As small businesses increasingly transact online, Shopify’s growth has exploded. Revenues grew from ~$670 million in 2017 to over $1.5 billion by 2019. The total number of merchants increased to over a million from under 200k in 2015 who had cumulative sales of over $60 billion in 2019. In the US, Shopify is the second largest e-commerce platform in terms of cumulative sales of all businesses running on the Shopify platform.

A stupendous feat considering that Shopify does not have consumer-facing marketing and all the customer acquisition is done by the businesses themselves.

To be clear though, there is a long path ahead for the company to traverse. In 2019, Amazon clocked $280 billion in revenues of which ~$245 billion was in product and service sales (remaining ~$35 billion was in AWS).

So, it is early days. Yet there is a promising business model here. Being digital-led, the business has a high margin profile. Shopify breaks out its revenues into subscription and merchants solutions (fees from payment gateways, shipping, warehousing). Overall gross margins stood at 54%. Margins from subscriptions were over 80% while the margins for merchant solution were unsurprisingly lower at ~37%. While it reported an operating income loss, that was due to the company’s investments in marketing (~1/3rd of the revenue) and R&D (~1/5th of the revenue).

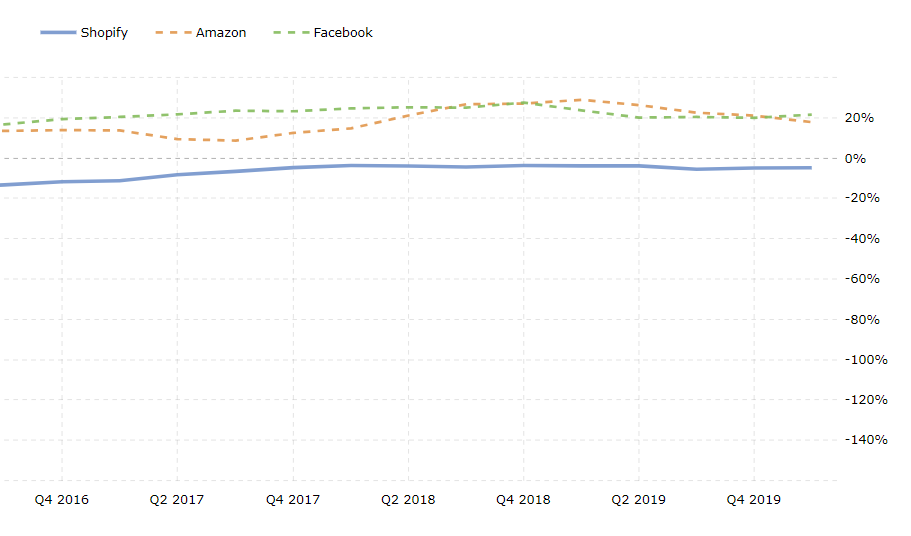

A measure of the company’s financial efficiency is Return on Equity (net income/shareholder equity). I have compared its RoE to Amazon and Facebook below.

As a high growth company, Shopify has negative net earnings leading to an RoE of -4% compared to that of Amazon and Facebook (and Walmart) that stands at ~20%. However, it is common for commerce companies to sacrifice profit at the altar of growth (a playbook perfected by Amazon for many years). In fact, Amazon’s RoE for the last 10 years has fluctuated wildly, ranging from -2% to 28%.

To summarize, there is a long way for Shopify to go but there are shoots of a promising, high growth and high margin business here. As its merchant’s solutions revenue scales, the overall margin profile will compress, but the subscription business, also a significant contributor, will boost the bottom line.

Why does it matter?

Benedict Evans, one of my favourite tech thinkers, makes a case that while Amazon has 35% of the share of the e-commerce market in the US, it only has a 5% share of the total retail addressable market. The point he states that there is a big field still left to play for and platforms like Shopify represent ways in which market share can be captured.

From Ben Thompson again

This is how Shopify can both in the long run be the biggest competitor to Amazon even as it is a company that Amazon can’t compete with: Amazon is pursuing customers and bringing suppliers and merchants onto its platform on its own terms; Shopify is giving merchants an opportunity to differentiate themselves while bearing no risk if they fail.

Tobi put it succinctly in an iconic reply to the question of being compared to Amazon.

“Amazon sells things to customers, Shopify doesn’t. Amazon is trying to build an empire, Shopify is trying to arm the rebels”

The rise of alternate platforms

The pandemic is an industry-defining moment for online commerce. A strong narrative sells and the likes of Shopify with their custom-built solutions are finding increased adoption. Even platforms such as Etsy, an American e-commerce website focused on artisanal vintage and craft supplies is seeing a boom. It is now also a destination for baked products from homebound chefs. Its customers like that they are buying from ‘real people and small businesses’ and are willing to pay higher prices for it.

India itself is going through an interesting transition. While the tale of Amazon and Flipkart is well known, Facebook’s investment in Jio will mark the onset of platform wars in the country. The investment might be a catalyst for Reliance to accelerate its ambitions to digitize the big vanguard of offline retail – neighbourhood Kirana shops. Imagine a transaction flow where a customer browses through the inventory of a Kirana shop on Whatsapp, selects the desired items and pays either through WhatsApp or in cash for an order that is fulfilled through Reliance delivery networks.

It can go further still. Facebook also announced a partnership with Shopify to allow merchants to easily set up a digital storefront on Facebook and Instagram, with the backend powered by Shopify.

Over 6 million small businesses are listed on Facebook in India. Shopify’s backend, WhatsApp’s and Facebook’s widespread digital penetration, coupled with access to cheap data due to Jio might be the fillip that small businesses need to complete their digitization journey.

By no means, are they alone.

Take, for example, Instamojo. Started by Sampad Swain as a payment gateway, it has evolved to serve the needs of small businesses including freelancers, to enable them to digitize their offerings through payments, online cataloguing, custom digital storefronts, order invoicing, financing among others. It is rapidly adding features and seeing strong traction. It already has over a million merchants on its platform and aims to reach 10 million in the next three years. Achieving that feat would make its growth more stratospheric than that of Shopify itself (though revenues would not match that of Shopify due to overall lower 1) transaction volume in India, 2) subscription prices and, 3) adoption of subscription models). For the transformation it can create, it’s a vision worth rooting for.

Digitization is inevitable. Platform companies are powering this transition taking the opposite philosophy of large marketplaces. It will be a journey with interesting product launches, exciting product choices for customers and a vibrantly competitive market to attract merchants. These companies will not only create value for the businesses they power but also become powerhouses themselves. Watch out for the rapid rise of e-commerce platforms who arm the rebels.

In other news,

A round-up of a few interesting articles I came across this week

Food delivery apps have permeated our lives. What if millions of dollars in venture capital has gone to fund an industry which is fundamentally broken? Ranjan Roy makes an interesting case. Doordash and Pizza Arbitrage

A delightful read in the NYT on the Baklava makers of Istanbul. In Istanbul, Baklava makers are essential workers. Given that they produce something so life-altering, why wouldn’t they be?

Last week, I made a case that the economic impact of pandemics is in essence, history repeating itself. Turns out, that is true for art and culture as well. How pandemics have inspired art, music and literature.

Spotify signed a $100 million deal with Joe Rogan to bring the world’s most popular podcast exclusively to its platform. Joe Rogan has probably been ripped off by Spotify. Always control your own distribution (Yes, writing on Substack, the irony is not lost on me).

A joke as hilarious as this can be fatal.

The newsletter takes time and effort to put together. If you like it, please share it with others, tweet about it and send me feedback at romitnewsletter@gmail.com. It keeps me going. Stay safe!